I would like to preface this article but asserting that I am not a psychologist, instead an avid student of beauty through art & design and indeed life itself. My sensibility favours the multi-sensory brand of beauty. I advocate for the kind of beauty not only limited to the faculties of sight and vision, but the kind available to any attuned and sensitive student for whom an embodied appreciation of beauty is alive..

…

Beauty (n): the quality or aggregate of qualities in a person or thing that gives pleasure to the senses (especially the sight) or pleasurably exalts the mind or spirit.

When it comes to the question of Beauty, the word alone evokes a universe of perspectives. Whether viewed through the lens of neuroscience or aesthetics, beauty continues to be a slippery topic of sensory perception, and yet its influence resonates across every aspect of life; from the aesthetics of art and design to chemistry and attraction.

There is no shortage of theories about what makes an object aesthetically beautiful. In the realm of art & psychology ideas about proportion, harmony, symmetry, order, complexity and balance have long been studied by artists and psychologists alike. However despite this longevity, perceptions of beauty are often still limited to the faculties of sight and vision and there is little conclusive evidence about what it is that makes something perceived as beautiful.

In his book The Sense of Beauty published in 1896, Georges Santayana defined beauty as “objectified pleasure”. Counter to previous schools of religious and spiritual thought, Santayana argued that beauty is not a question of philosophy, but a human experience based on the senses and is quintessential to fields of aesthetics.

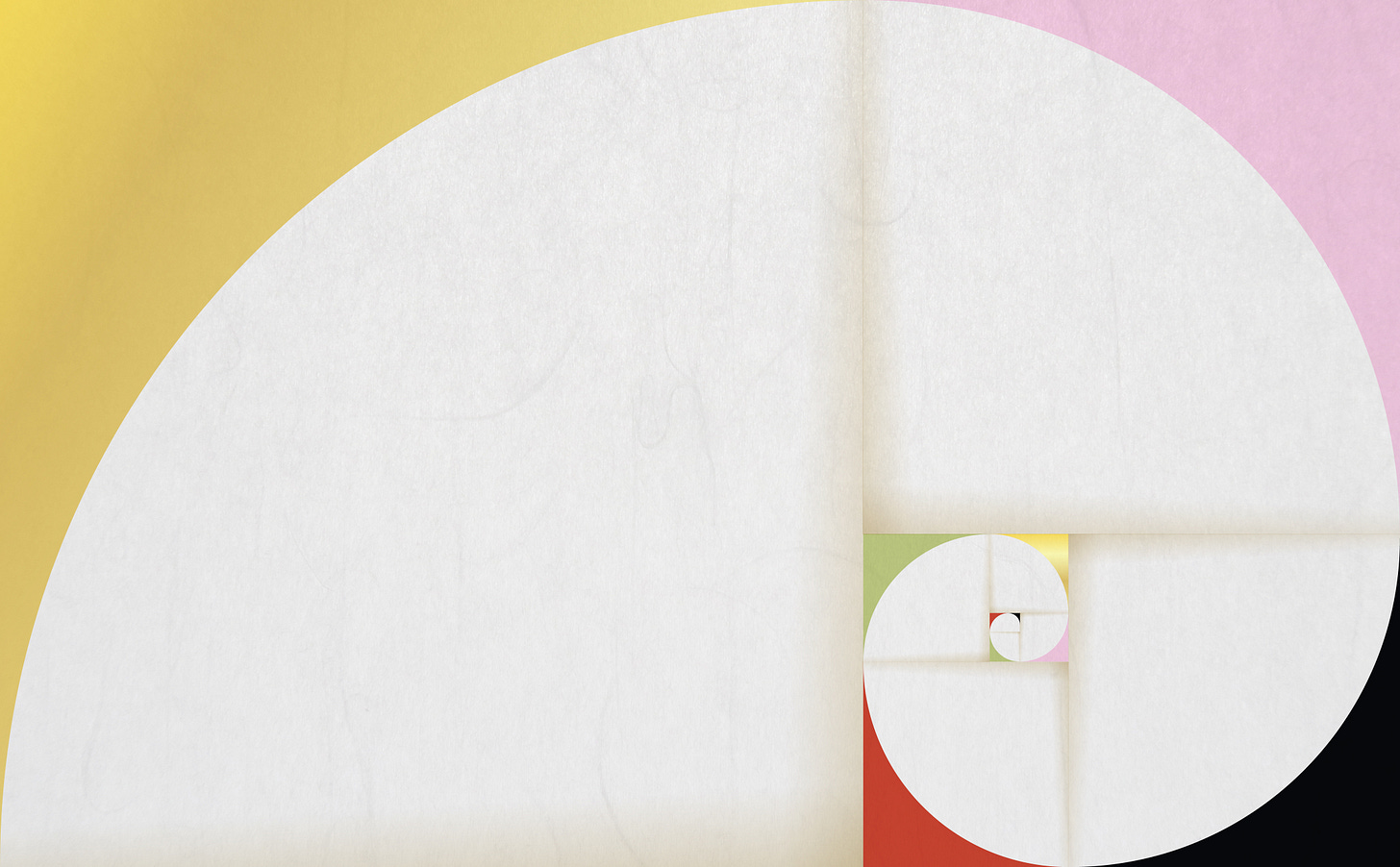

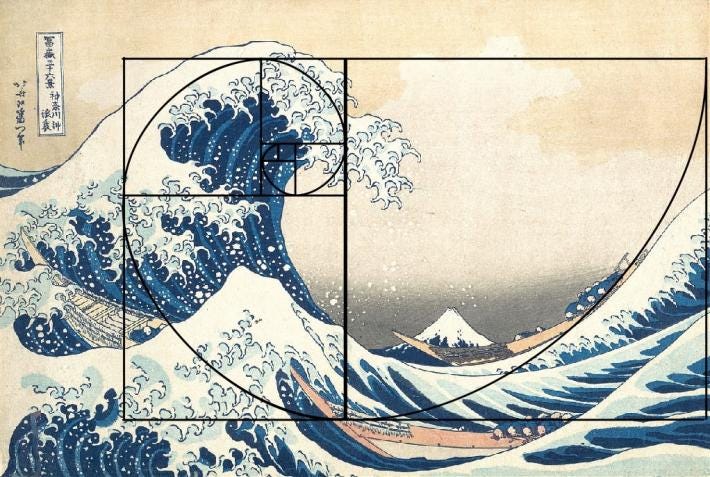

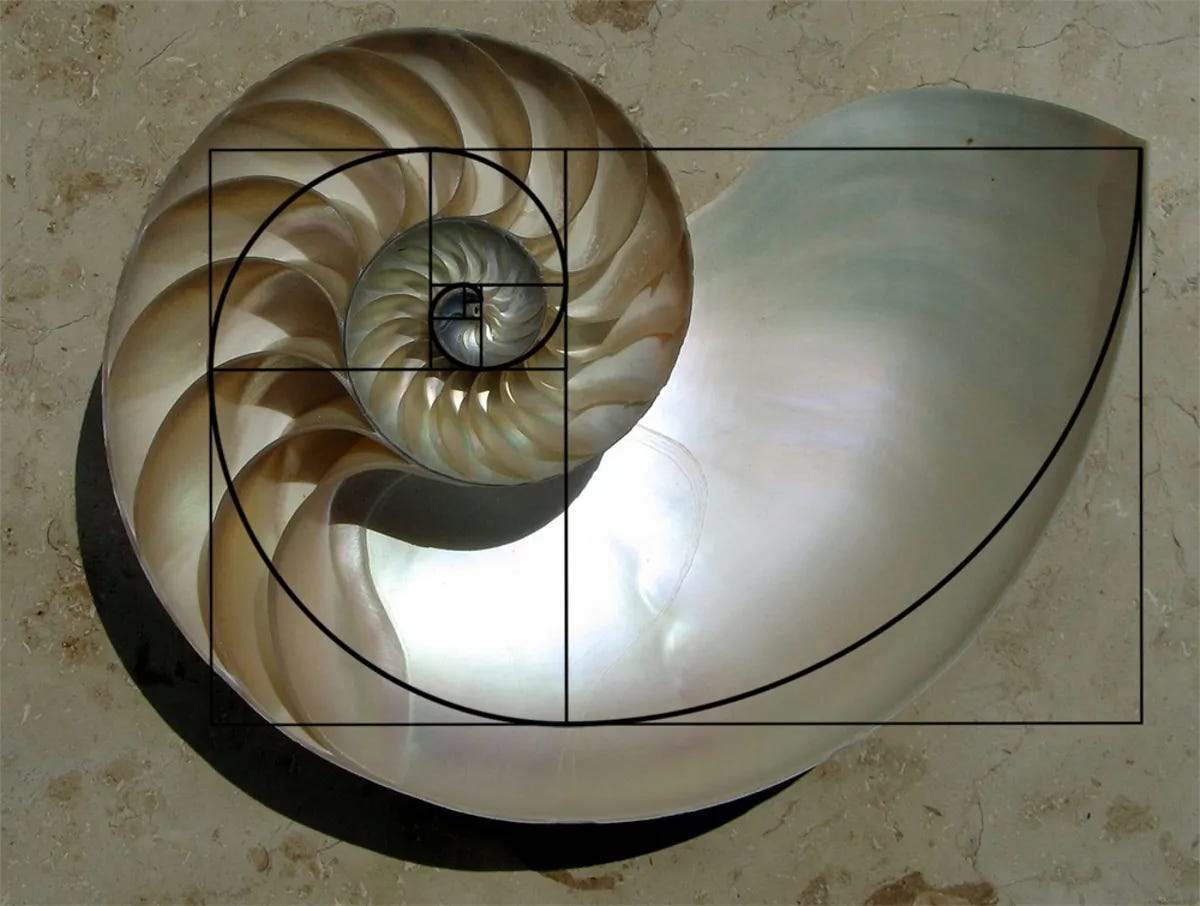

One of the dominant players in the exploration of beauty is through the lens of Psychophysics, that is the study of the brains’ response to physical stimuli and its perceptual phenomena. Psychophysics has long been concerned with environmental factors on perception, including the mathematical patterns found in the natural world. The Golden Ratio, (also referred to as the Divine Ratio) refers to a ratio between two numbers that equals approximately 1.618. The Golden Ratio is an algorithm of proportion that is found recurring in Nature; from seashells, to sunflower spirals, from leaves to pine cones and it has long been considered a mathematical distillation of beauty.

The Golden Ratio was first referenced in Euclids’ Elements, a master work in early mathematics and geometry. However it wasn’t until In 1509, when Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli published the book De divina proportione, accompanied by illustrations by Leonardo da Vinci, that the ratio inspired futher representation across the world of art, architecture and design. 20th-century artists and architects, such as Le Corbusier, Salvador Dalí, Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, have all utilised the golden ratio or its counterparts, such as the golden triangle to achieve aesthetic balance, simplicity and divine order within their work.

In 1876, alongside his study of “outer psychophysics”, German psychologist Gustav Fechner, shone light on the mystery of “inner psychophysics”, relating to the internal states of the nervous system and the subjective experiences that evokes them. Simply put, despite his application of patterns such as the golden ratio, he came to infer that beauty was indeed a subjective experience.

In a recent study, researchers from the Tsinghua University in Beijing undertook a study to examine the origin of beauty to further explore whether it was possible to isolate a specific “beauty centre” within the brain. Furthermore, whether this neural centre could be consistently mapped when stimulated by images of beauty, both in faces and in art. There were consistencies across their test group, where different centres of the brain were repeatedly activated by the beautiful stimuli, however these areas were non-overlapping, suggesting that the beauty of a face is not perceived the same as the beauty of a piece of art. This study also supported the notion that beauty is not only subjective to the viewer but may also be particular to the medium.

Often when we speak of beauty, we are speaking to more than just sight, beauty is rarely about “pretty”, beauty is what we find visually or sensorially compelling. Like Santanaya, I believe that the roots of what we find compelling lies within the intersection of both the physical and the subjective; that is a combination of what we perceive (the external) and the subjective make up of who we are (the internal).

Beauty from an evolutionary point of view may yet be the perception of what is safe, what is familiar and what is perceived as nourishment. This input of perception may be dominant through the eyes, however could we consider beauty as something that activates the entire spirit, received through sound, scent, taste, touch or the nervous system. Our sensory perception finds rest in natural environments because nature inherently works in patterns and rhythms. A shoot, becomes a stem, becomes a branch, becomes a tree; the same patterns, such as the golden ratio are repeated on scale. This repetition is medicine for the eyes and in turn our minds. Cities and urban environments are visually chaotic, irregular and unnatural in their visual language, and it takes more energy for our eyes and in turn our minds to process. Beauty therefore may not only activate the faculty of sight but a state of the body and nervous system in response to what is familiar.

Despite the varying schools of thought, it seems to be congruent that nature and beauty are intertwined. When it comes to the commercial world, despite radical questions of taste and trend, if the intention is to create products, spaces or experiences that evoke our innate perceptions of beauty (or even more so to subvert them) it would be wise to look to nature. Once again the multiverses of art, design, science an nature share the keys to impactful and meaningful design. May we design with our faculties of awareness activated and engaged, just as nature intended.

The Golden Ratio / Image via Adobe assets artist: rrice

The Great Wave / Katsushika Hokusai, Japan, ca. 1830–32

Image: Chris 73 / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Cover Image: Frederick H. Evans Section through a Shell of the Nautilus 1900-1915 (likely) Gelatin silver print 21.9 x 17.0 cm. Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc. LL/30029